Bovine Adenovirus (BAdV) in R1 Dairy Calves

/HISTORY

We recently had a case of BAdV confirmed in a mob of 140 rising yearling dairy replacements. Five rising yearlings had died over a period of 3-4 days. Unfortunately, four of them had died over the previous 24-48 hours during a very warm spell of weather, and when found were too autolyzed to postmortem. The fifth calf, noticed late the next day, was acutely unwell, and subsequently examined, treated and blood tested/faecal sampled. The calf had a high temperature, dull demeanour, dehydrated, diarrhoea and unable to stand unaided. This calf died overnight. The mob’s drenching history was up to date, and unlike a lot of reported cases of BAdV, where the mob has been unwell, the remaining calves appeared in ‘good health’.

THE DISEASE

BAdV is a relatively uncommon disease – but was noted as a disease of increasing occurrence in rising yearlings in a national review 10 years ago. It is a viral disease that is mainly seen in 6-12 months old calves. Outbreaks, usually with low mortality rates (1-3%) can occur during autumn, winter and spring months, and often post weaning. It is primarily an acute gastro-intestinal disease, but calves may also have respiratory signs.

Adenoviruses are transmitted in nasal and oral secretions and faeces. While many cattle are infected, only a small proportion develops disease, which are animals usually immuno-compromised or have concurrent BVD infection. Common differentials for BAdV are Yersinia, Salmonella, BVD/mucosal disease, GI parasites, and other causes of acute death – nitrate poisoning, clostridial disease or toxicity.

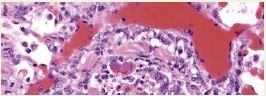

DIAGNOSIS

Until recently, the main way to diagnose BAdV, has been getting good quality bowel samples and doing histopathology – and seeing the classic inclusion bodies, of this disease. However, a PCR (looking at genetic material) blood test is now available – and markedly assists us with the diagnosis. The fifth calf was positive for BAdV, and it was assumed it was also the cause of the other four calves that died.